If you lived through the 1980s, you will understand the strange and special thrill of receiving a concerned voice mail from Huey Lewis. “I’m going to see you tomorrow, but I need you to drive real slow,” Huey tells me, his indelible rasp turned fatherly. “There are a couple three days a year when the roads are really bad, man. And you’re in ’em.”

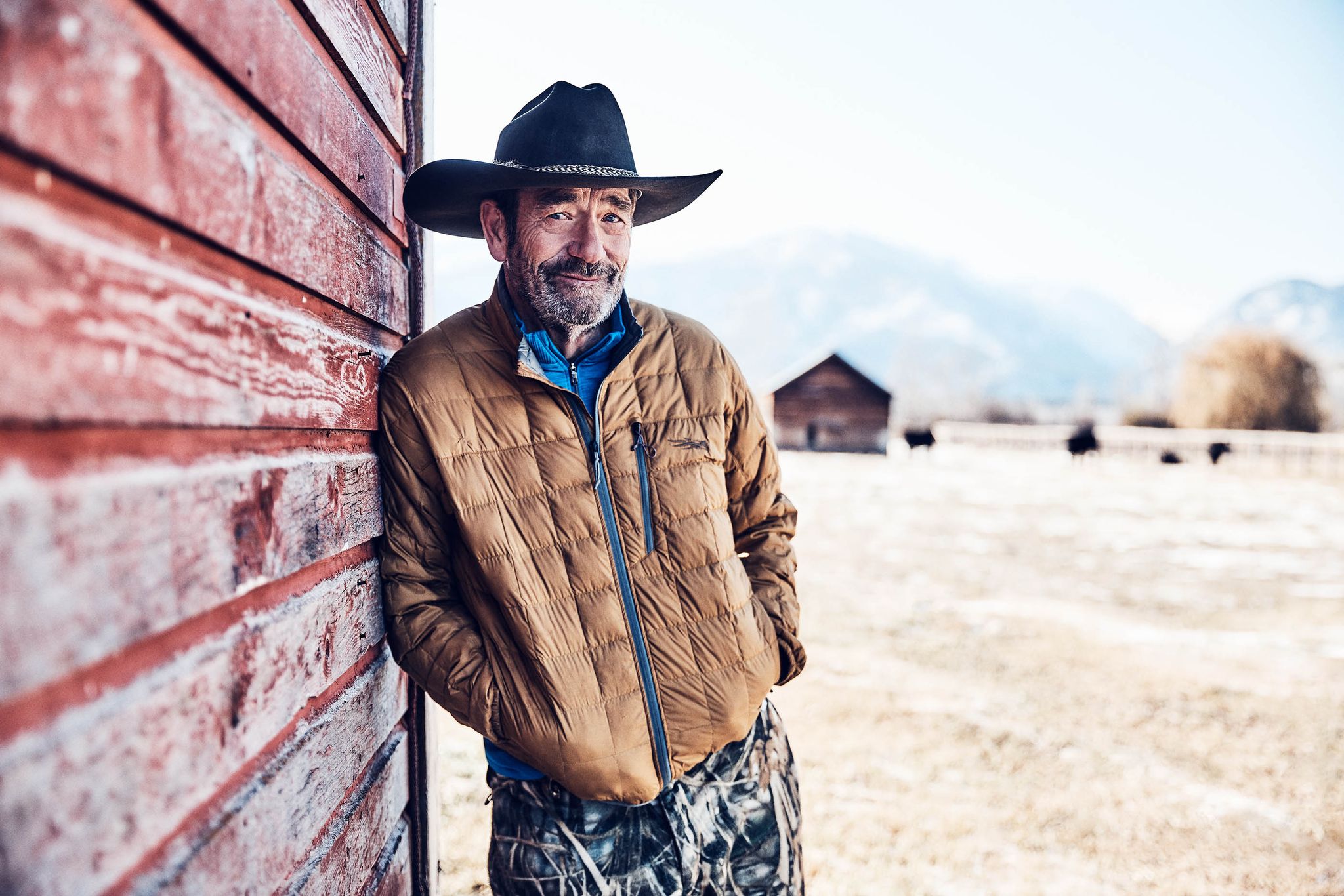

It’s 5 degrees the next morning when I drive to his ranch, an hour outside Missoula, Montana, on narrow state highways as much ice as road. When I pull in—carefully, as instructed—there he is, a solitary figure standing in the snow, an icon in camouflage, surrounded by snowcapped mountains. This is a place where Huey can do what he likes while he waits to find out whether he’ll have another chance to do what he loves.

We’re months away from the release of Weather, the first album of original Huey Lewis and the News music since 2001, and Huey doesn’t know if he’ll be able to perform again. Two years ago, he lost the ability to hear amplified music, to find pitch, to sing live. “When it’s really bad, I’m completely deaf almost,” he says. The title Weather was originally a nod to age and to the band’s breakthrough, Sports, but there’s a newer meaning than what we’re used to getting from Huey. It’s possible that with a lot of living still ahead, his last gig is behind him. “We’re getting a little weather now,” he tells me. “It’s not a perfectly clear day.”

He shakes it off. “You wanna go on a sortie?”

Huey sizes me up and grabs some cold-weather gear out of his mudroom, and suddenly I’m bouncing around a Montana ranch in an ATV wearing Huey Lewis’s snow pants. His house looks like a traditional suburban home—Rick Reilly’s Trump book Commander in Cheat on the kitchen island, one of those rooster-shaped wire baskets full of keys and chargers, a picture of him with Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott on the counter to remind me I’m in a rock star’s kitchen—but it’s on a massive expanse of land not far from the Idaho border. He bought the property in the eighties and made it his home in the early 2000s after he and his wife split up, the kind of middle-of-nowhere place that makes a person understand the appeal of the middle of nowhere.

As we bob around the duck blinds, over the irrigation ditches, he points out a bald eagle in a tree, a herd of whitetail deer bounding past. He’s content here. This is entertainment for Huey now that he can’t hear television or music.

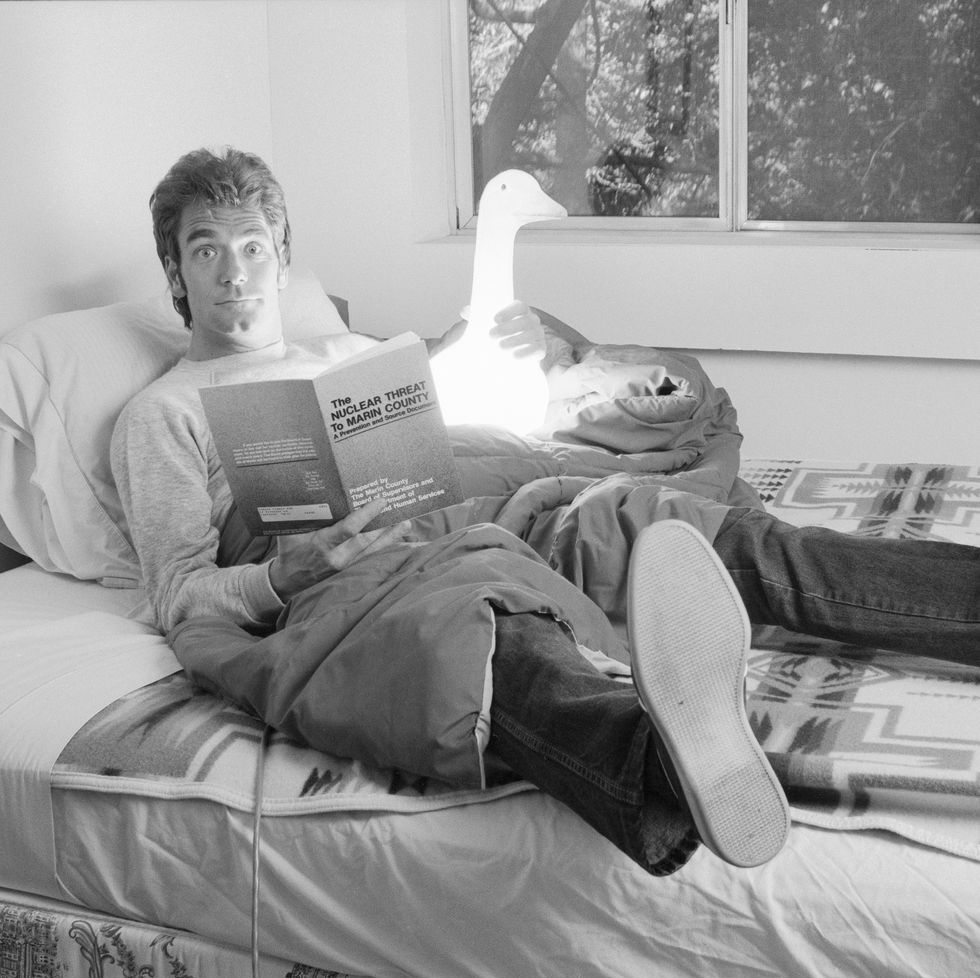

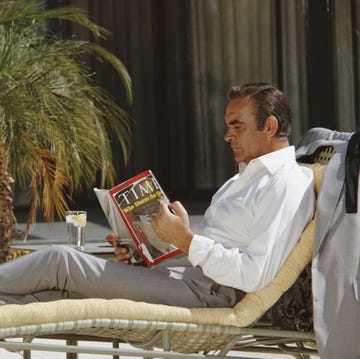

It’s particularly cruel that music sounds like distortion to him, because the albums he made with the News were meticulous pop-rock, with the smoothest harmonies this side of the Beach Boys. It’s difficult to imagine from today’s perspective, but after the release of Sports in 1983, Huey was ubiquitous and well-liked. He had every subset of the 1980s American teenager on his side, like he was Ferris Bueller’s cool uncle. To know Huey Lewis and the News was to love them, whatever else you naturally enjoyed. You could, like me, not play sports and play the hell out of Sports. Huey represented a sensibly sexy mainstream masculinity: dimpled chin, haircut that rejected any recognizable trend, body just Soloflexed enough to pull off a red suit. The coolest guy at your dad’s work. He’s still craggily handsome as he approaches his seventieth birthday, a hero in a Clint Eastwood western.

"HUEY, A PLAYLIST BY DAVE HOLMES, CURATED BY HUEY LEWIS

“Those videos when we were teenagers all watching MTV at all times were just so appealing. The songs were great to sing along to, and the guys seemed to be having fun,” says his friend Jimmy Kimmel. “I just think Huey brings to mind a better time.”

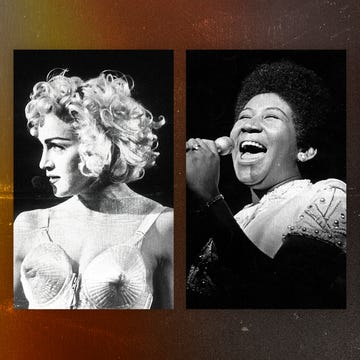

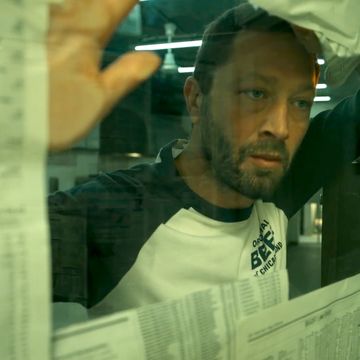

In his upstairs office, among a few American Music Awards, a poster from his run as Billy Flynn in Chicago on Broadway, and the band’s one Grammy for Best Long Form Music Video, is a framed copy of the top two hundred albums from Billboard magazine’s June 30, 1984, issue, the week Sports finally hit number one, nine and a half months after its release. Behind Sports in the top ten: Van Halen’s 1984, Thriller, Born in the U.S.A., the Footloose soundtrack. Purple Rain was released that week; Madonna would debut “Like a Virgin” at the first Video Music Awards weeks later. “This is the good stuff,” I sigh out loud. Summer 1984 was possibly the greatest summer in pop-music history, due to the genre gumbo of MTV and Top Forty radio.

It was the height of the monoculture, and Huey sat on top of it, with weapons-grade likability and a sound that didn’t quite conform to the trends. Although he gets lumped in with the superstars of the eighties, the songs of Sports—“The Heart of Rock & Roll,” “Heart and Soul,” “I Want a New Drug,” “If This Is It”—don’t sound dated. They don’t even sound like the sixties R&B that inspired them. They’re timeless. “A lot of the songs we wrote in our twenties and early thirties are actually more appropriate for a guy in his fifties,” Huey says. I nod excitedly, a guy in his forties who devoured the album when he was twelve.

Huey’s always been a man slightly out of his moment. He grew up mostly in Marin County, California. (If you are of a certain age, this is a thing you know, because Casey Kasem would say it over and over during the year and a half Sports pitched singles up the Top Forty.) Its proximity to San Francisco brought in its share of hippies, a counterculture for Huey and his friends to rebel against. Huey’s mother was one of the first Deadheads; she dabbled in hallucinogens and dated Charles Mingus when Huey was a teenager, after she divorced his father, a radiologist and jazz drummer. “We had to find our own thing,” he says. That thing was the local soul station, KDIA, its playlists thick with the music of Stax Records.

He left the West Coast after high school to busk around Europe for a year. “I played harmonica until my lips bled,” he says. Then he was off to Cornell University in upstate New York, before dropping out sophomore year in favor of more travel and more busking. (His father approved: “You need to woodshed on that harmonica, man,” Huey remembers him advising, well into the late eighties. “That’s something they can’t take away from you. This Huey Lewis shit is here today, gone tomorrow.”) He went back to London for a longer stay in the mid-seventies with his country-rock band Clover, just as punk was about to rip a hole through popular music. “Almost the day we landed in England, Johnny Rotten spit in the face of the first NME reporter, and the game was on.” The music wasn’t for him, but the punk spirit was. “With the punks, I saw these kids just thumbing their nose at the music business. They were just going, We don’t give a shit what you guys think. We’re going to sing our own songs our own way. And I thought, How liberating. And I vowed if my band ever broke up, that’s what I was going to do. Go back to Marin County and surround myself with my favorite R&B-based guys, and we’ll just play our local pub and see where the chips fall. That’s exactly what we did.” And that’s how I found out the guy who wore a polo shirt and black jeans to the beach in the “If This Is It” video was influenced by punk rock.

It makes sense. Huey’s more of a risk-taker than his spot in the mainstream would suggest. He convinced his label to pay for an unknown Stevie Ray Vaughan to open for the Sports tour. (The fans weren’t ready for it: “He’d be burning it down, and the crowd would go, ‘Huuuey, Huuuey.’ It was the weirdest feeling, hating your audience.”) He touted Bruce Hornsby to indifferent record labels before finally producing three tracks on Hornsby’s debut album. Nowadays, Hornsby drops by the ranch and plays some Bill Evans tunes on the living-room piano. “He’ll just take your breath away, man.” Huey has been told good things about Hornsby’s excellent 2019 album, Absolute Zero, “but I haven’t heard it all, because my hearing is so fucked up.”

For the past three decades, Huey’s been relying on one good ear. His right one went out just before a gig in Boston in the mid-eighties, and a specialist in San Francisco told him to get used to it. “You only need one ear,” he says. “Brian Wilson had one ear.”

Then came January 27, 2018.

Huey was backstage at a News gig in Dallas, and all at once the opening act turned into distortion. “They’re playing, and it sounds like it’s warfare ... like there’s an airplane taking off.” He went through with the gig, but even the sound in his in-ear monitors was a jumble. He couldn’t find pitch in his own music. “It was the worst night of my life.” An ear specialist put him on a steroid regimen for twenty-eight days. No change. He saw a rheumatologist, then an immunologist, then an otolaryngologist at Stanford. The best any of them could do was to diagnose it, and barely. “They tell me I have Ménière’s disease, but nobody knows what Ménière’s is. It’s a syndrome based on the symptoms. If you have vertigo, stuffed ears—like it feels like you just got out of a swimming pool—and hearing loss and tinnitus,” all of which Huey has experienced, “then they call it Ménière’s.” He shrugs. “But they don’t know what it is.” They also don’t know what causes it or how to cure it. His doctors have put him on a low-salt diet, but he’s not sure it’s helping. The condition might go away as it came on. It also might not.

His friends and family call and text with ideas, specialist referrals, supplements—and around 100 percent of the time, he’s already checked the idea out. There’s a new bottle of supplements on the kitchen island courtesy of Kimmel. “Jimmy said, ‘Jen Aniston’s taking it.’ I said, ‘Bingo. Whatever Jen Aniston’s taking, I’m in.’ ” (It was a bit of a trick, admits Kimmel, who befriended Huey years ago after meeting him at a News gig: “I actually turned her on to those, but I knew he’d like hearing Jennifer Aniston takes them.”)

Two years have passed since Huey has done a proper gig, and the musical energy is all pent up. As we stand around his kitchen island, he summons music on his phone from a seventies-era act he loves called Rance Allen Group. Then he starts singing along: “Ain’t no need of crying when it’s raining,” Rance and Huey sing to me, “ ’cuz crying only adds to the rain.” Then the harmonica comes out, and he starts playing along, and there is so much pure joy radiating from him—a guy I love doing the thing he loves—that I’m almost sorry I’m going to die in his kitchen.

We can have this moment because the track is compressed, hitting our ears with the force of an iPhone speaker. “Doing this with a proper band,” he says, “with bottom end and drums roaring away and all that? That’s going to be hard.” Huey wears hearing aids that play a series of five tones when he puts them in each morning—“It’s an F chord,” he tells me—and if he can hear all of them, that’s a level 6 hearing day. Today is his twenty-fifth level 6 hearing day in a row, a new record. If he racks up another week or two of 6’s, he’ll try to sing along to loud music. “What I got to do is get stabilized for a month, and if this works, then we’ll try a little rehearsal experiment. If that works, then we’ll try a full-blown rehearsal. If that works, then maybe book a gig. But I’m a ways away from that yet.”

The music went away slowly and then all at once. So what if it never comes back?

“I haven’t allowed myself to go there yet,” Huey says, worry in his voice. “I keep thinking I could maybe sing again. I get down sometimes, but it’s better to remember that life is okay. I’ve had a great run.” He is as upbeat as a man can be when he’s beginning to speak about himself in the past tense.

The temptation is to paint Huey as a tragic figure, out in the middle of nowhere, waiting to see if his music career can come back to him as quickly and mysteriously as it left him. But I don’t want to write a tragedy, not about Huey Lewis. A positive outlook is the one thing all the doctors have prescribed, and after all the plays I got out of Sports and Fore! and Picture This, I owe him mine. If you know Huey, then you love him, and what is love if not belief and support?

When we check in several weeks later, the goalpost has moved again. “I had to cancel rehearsal,” he texts me. After nine weeks at a 6, three days before his first attempt to sing along to live music in two years, his hearing went to a 2. All at once. He doesn’t know why, and the doctors don’t either. The guy is curious and passionate about a million things—“He’s very smart about any number of subjects,” Kimmel says, “by which I mean all subjects”—but the one mystery he can’t solve is the one that keeps him from singing.

So now we wait to find out whether there will ever be another Huey Lewis and the News gig, and as we do, all we know for sure is that there ain’t no need of crying when it’s raining. In the meantime, Huey’s just being patient, trying his hardest to adjust to the quiet.

A version of this story appears in the March 2020 edition of Esquire. Subscribe